Photos by Jan Chlebek

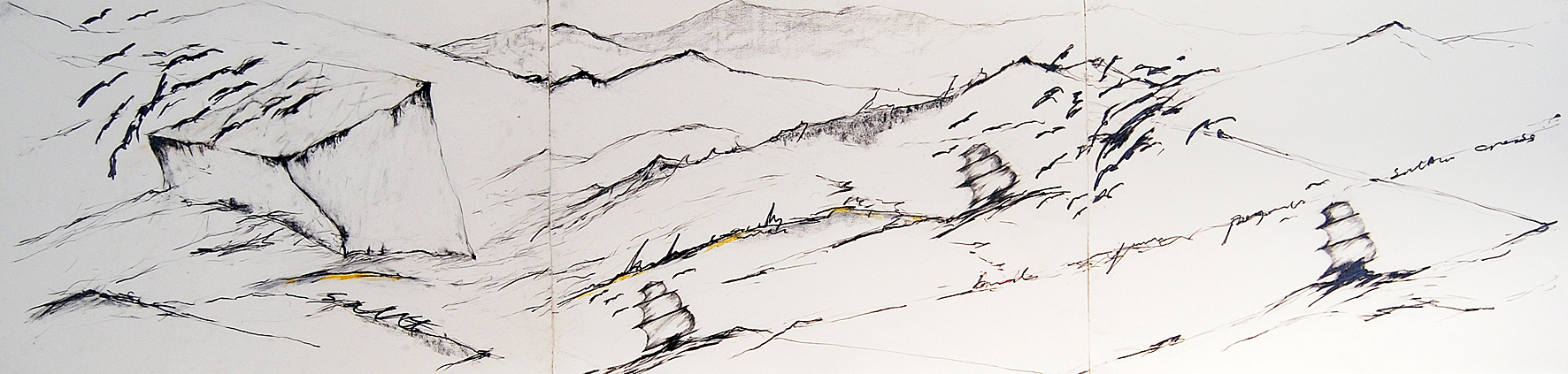

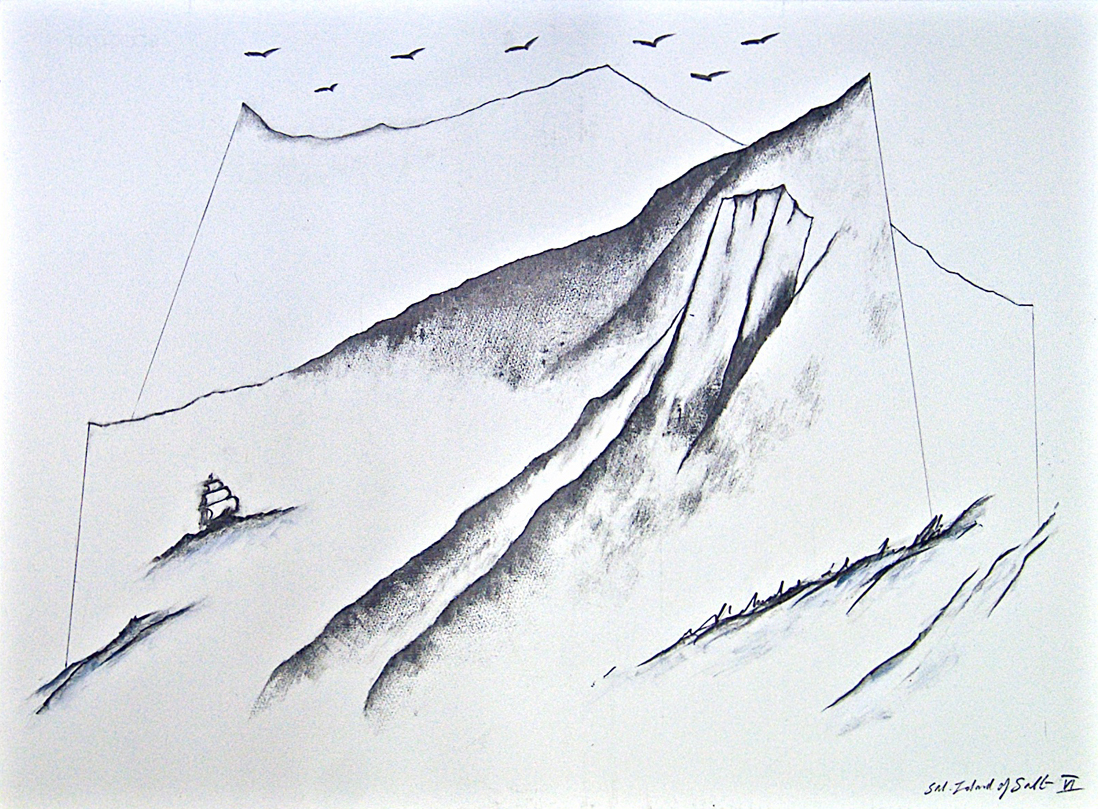

Here is a landscape populated by the wings of birds. (Much of my work might be characterized as “a commonwealth of wing,” to use the phrase of Edward Fitzgerald, the translator of Omar Khayyam). Here the landscape is salt-white, stark as chalk, a place leached of colour where even the rectangular forms are blurred and studiously imprecise. A stony place such as the bare Greek headlands Seferis loved. The eight canvasses stand together in seemingly casual sequence while the shattered whites and smudged greys are interrupted by strategic spaces—caesuras that enforce a pause on the visual rhythm of the eyes. The three canvasses above form a tryptich; they too are distanced by a caesura that enables them to be read as a quotation over the main body of the essay. In the handwriting embedded in flake and titanium, we read the words—insistent in their black graphite—“ inhabited only by birds”. We remember that in Virgil’s Aeneid, the entrance to the underworld, to Avernus, was called “the birdless place.” Here, for all its muted sorrow, is a place aswarm with birds. Tilted against these tablets are long crooked sticks that serve as flying buttresses, capped by gargoyles suffused with a vague and disquieting pathos, an anguish shaped out of rags and wax. But who are these hooded figures reminiscent of the river god in Rome’s Piazza Navona, its head wrapped in cloth? They are simultaneously frightening yet sad, menacing yet vulnerable. Do they evoke that “infinitely suffering, infinitely gentle thing” that T.S. Eliot once imagined? This visual paradox lies close to the heart of Levantis’s art: what is most threatening, most terrifying, is also what elicits our deepest pity. “Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous,” as Nathaniel West wrote.